“Life holds only one tragedy, ultimately: not to have been a saint.”

Charles Peguy (1873-1914)

To be perfectly honest, I often find reading about the saints disheartening.

Which obviously defeats the purpose. Learning about their lives should be inspiring, but it seems many of the books or articles that describe those now in Heaven go something like this: “Saint Oswaldo was born into a wealthy family, but at age 11 decided to renounce all his possessions. Throughout his life, he consumed three ounces of rice per day and wore a loincloth and hairshirt, sleeping only when he stopped preaching to lepers. He founded an order, built six schools, and translated the Gospel into 13 tribal languages.”

Of course, this is an exaggeration. But it represents something very real—that often saints are made to appear these mythical characters with the resumes of Nobel Prize winners. They’re supermen and superwomen.

And this isn’t necessarily wrong: They are heroic in their virtue, driven to incredible heights thanks to the grace of God. They did transform the world with the orders they founded, the schools they built, the poor they fed, the books they wrote, and the hardships they endured.

But this often discourages me, because it makes me think I’m a lost cause. I’m no mystic. I haven’t founded any worldwide charitable institution. I haven’t preached to lepers. Heck, I have a tough time getting through a Hail Mary without thinking about the weather or last night’s ballgame. Basically, these inspirational stories of the saints—instead of breathing life into me—are deflating: You’ll never be that great. Just look at yourself.

And that is why I love St. Joseph so much.

Among the extraordinary titans of faith, among the mystics and popes and abbots and abbesses, among those whose good works have been documented in the annals of history—among all of them, the most powerful saint in heaven besides the Blessed Mother is, at first glance, shockingly ordinary. Pope Pius VI called St. Joseph

“the proof that in order to be a good and genuine follower of Christ, there is no need of great things. It is enough to have the common, simple and human virtues, but they need to be true and authentic.”

That gives me hope.

How many spiritual masterpieces did Joseph of Nazareth write? How many organizations did he found? What was his noble profession? Confessor? Missionary? Soldier?

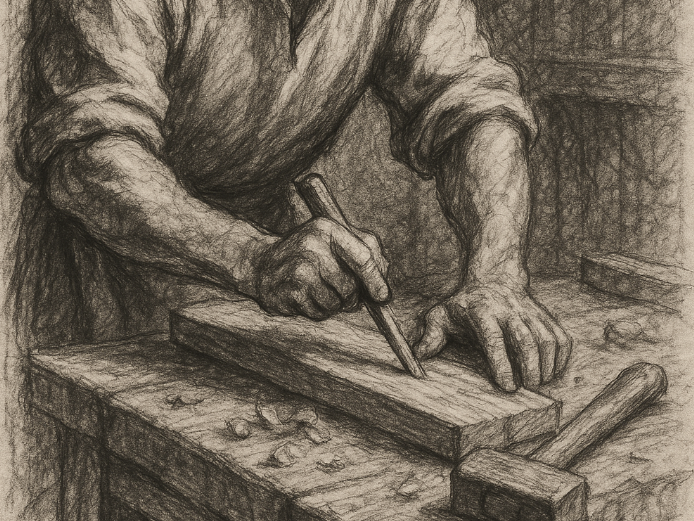

Nope, he was just a carpenter.

He made chairs, tables, and window panes. Where other saints traveled to faraway lands and were martyred as missionaries, he spent the bulk of his life in a small, oak-smelling workshop in Palestine—planing wood, sanding boards, sawing planks. As far as we know, he never made a sermon or wrote a word. He wasn’t known for eloquence or healing powers. He wasn’t martyred, either.

His life was a whisper.

Of course, Joseph was more than a carpenter—he was the saint whose great humility and faith prepared him for the greatest task of all time: protecting, feeding, clothing, and rearing the Son of God. And while his life had some fantastic elements to it—a dream from an angel, holding the Messiah in his arms, fleeing to Egypt—when those events had passed, Joseph passed the remainder of his life in a way that, to the rest of the world, probably looked mind-numbingly boring. Wake up, say a prayer, eat breakfast, repair the table, eat lunch, sand the drawer, say a prayer, sweep the shop, go inside for dinner with your wife and son, pray together, clean, and finally, go to sleep dog-tired. And repeat. For 30 years.

These 30 years that Joseph is believed to have been with Jesus in the woodshop were far from pointless, for in a sense they demonstrated the importance of silence, patience, and endurance. If the Redeemer of Mankind spent 30 years of his life with his dad sanding tables, then it must not have been for nothing. It must have carried with it great dignity.

Pope Leo XIII wrote, “Joseph, of royal blood, united by marriage to the greatest and holiest of women, reputed the father of the Son of God, passed his life in labour…it is then true that the work of the laborer is not only not dishonouring, but can, if virtue be joined to it, be singularly ennobled.”

Ennobled: yes. St. Joseph’s life as a worker, which we as Catholics celebrate on May 1st, attests to the utter strangeness of God, who has a way of flipping things around on us: Sometimes, doing the most important task can look and feel like the lowliest—cleaning up wood chips, filling out the paperwork, or driving the kids to dance practice. St. Joseph’s great trait, then, was his ability to recognize that all that really matters in the end is living your life in love and service to God, your family, and your neighbor, because this is what all true saints do. Sometimes that love for God will impel you to do something great—to build a school, to start an order, to write a book. But often it will simply tell you to clean the dishes cheerfully after dinner when you’re exhausted.

And so St. Joseph’s life seems to whisper something to all those who come after him: If the greatest tragedy in life is not to have been a saint, then perhaps the second greatest tragedy is thinking yourself too ordinary to be one.

Leave a comment